Published: June 20th, 2020 Last Modified: June 23rd, 2020

We all know the sheer joy of doing just a handful of minipreps at a time. You pull out all the flicks of the wrist and bits of finesse you’ve built over the years. Once you move past…oh…8 minipreps, and it becomes work. After 16 or 24 minipreps and you’re into re-evaluating your life choices. Those wash steps add up! What about midi-preps? Maxi-preps? Protein columns? Yeah, being able to process those in parallel in a efficient manner sure would be nice. In comes….THE VACUUM MANIFOLD!!!!

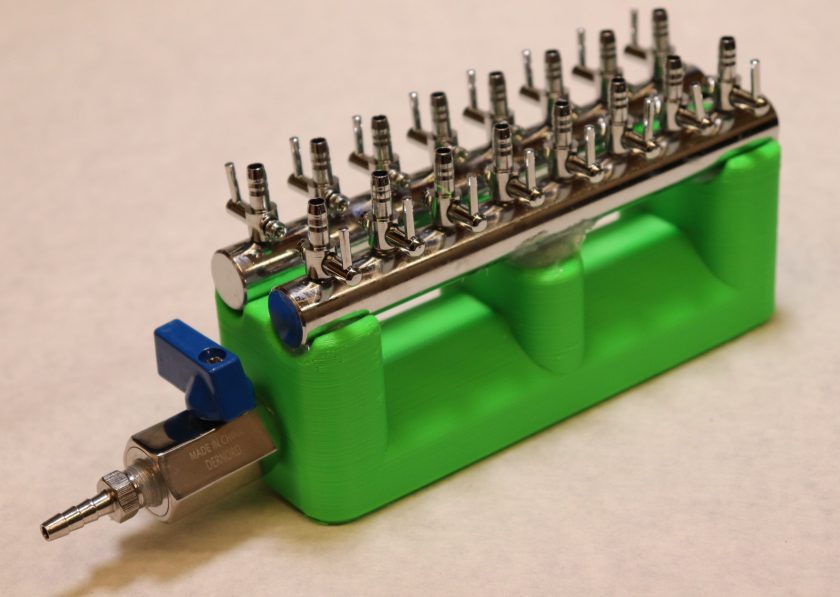

What does the beastie do? You apply a vacuum at the barbed connector, open the valve, and the vacuum is distributed between the little inlets, allowing you to suck away 16 columns worth of wash buffer at once! It’s not the cheapest build at 55$ worth of parts and access to a 3D printer, but considering alternatives start at 150$ and go into the hundreds, it’s worthwhile (and fun!) to build your own. Let’s go!

Parts List (?)

- 1x – 3D printed body, designed by yours truly (Link to zipped files)

- 2x – 8 Valve Air Manifold

- 1x – 1/8 NPT valve

- 1x – 1/8 NPT to barbed connector fitting

- An 1/8 NPT tap and tap wrench

- A 9mm and 10mm drill (If your 3D printer prints holes a bit undersized)

- Some RTV silicone, any brand

- An adjustable wrench, for wrenching

- A tubing cutter

- Some 4mm ID x 6mm OD silicone tubing

So, first things first, 3D print the body of the manifold. It holds all the pieces together and provides the channel for the liquid to flow. Ideally you want to print it in ABS since you can use acetone to seal leaks later…but we’ll get into that. PLA and PETG are easier to print, but harder to melt and seal. Print with 5 top and bottom layers and 5 perimeters. Seems like overkill but we want this thing vacuum tight…or at least as tight as possible off the printer bed.

Looking good, looking good. Now, let’s tap the outlet of the manifold to accept the 1/8 NPT valve.

Put a gob of silicone on the pokey bit of the valve and screw it into the manifold body.

Repeat with the barbed adapter, get it good and tight with the wrench.

Almost there! Put down a bead of silicone on the supports that will hold the body of each manifold. Grab one of the 8 valve manifolds and put another gob of silicone on the outlet. Insert the outlet into the corresponding hole. Repeat with the second manifold. Let the silicone cure for a few hours and you’re (almost) done!

Voila!

After everything’s cured it’s time to test for leaks. Open the main valve and close all the lil’ valves, attach a hose to the outlet and pull a vacuum. If you get down to -22 inHg then you’re doing pretty well, it’s plenty to suck out wash buffer. How does ours do?

FFFFFFFUUUUUUU—-

Only 19 inHg? Eh…this little pump can do better than that, there’s a leak somewhere. So much for vacuum tight off the printer. Wheres the leak? Stick it in a bucket of water and apply positive pressure.

Oh, COME ON. The leak is…everywhere? Okay, we’ve come too far to back out now, let’s seal the entire sucker. If you were expecting this (you should) you’d print the body out of ABS and smooth the outside with acetone, easy. If you printed with PLA or PETG you’re using huffing grade chemicals like chloroform. I had some of this clear coating stuff for coating jewlery, ended up working a treat.

That’ll do pig, that’ll do. The gauge shows the same vacuum with the main valve open or closed, so the leak is sealed. Before using the completed vacuum manifold we need to have an interface that seals between the miniprep column and the little valves. Commercial manifolds use luer-lock stopcocks, an expensive proposition if you need 16 of them. They’re hard to clean and are picky with the types of columns they’ll accept.

What’s a better approach? Little lengths of silicone tubing! For minipreps I recommend 4x6mm tubing (ID, OD), maybe have a 3x6mm for smaller diameter tubes and a 4×8 to handle heavier columns. The more rigid the tubing the more weight it can support. Cut up ~12mm sections and keep them in a lil’ box.

Okay, seriously, we’re ready now. What’s the whole setup look like??

Mmm, now I want some kool-aid. As you can see the silicone tubing holds the columns nicely, even a midi-prep sized nickle column! I tried a DEAE maxiprep column with the 3x6mm silicone tubing and it just barely held it, probably needed a 4×8.

The advantages of a silicone tubing interface is that they are easy to sterilize en-masse with decon mix, and if you lose one…oh well! Cut off some more! Let’s see it in action.

Woohoo! Look at it go!

One last thing, here’s how you generally set up a liquid trap AKA aspiration apparatus to avoid getting corrosive juice in your vacuum pump.

Now, the manifold is a tool, and just like any tool it pays to have a bit of practice before applying your precious samples to your columns. Things I’ve learned:

- The vacuum manifold does not eliminate the need for a centrifuge for little spin columns. There will still be a little bit of leftover buffer that will NOT go away on it’s own. After washing your silica columns you need to centrifuge them for a few minutes to remove traces of wash buffer. Also, you will need the centrifuge when you transfer your spin column to a fresh 1.5mL tube for elution. For massive amounts of minipreps you are saving time in washing/taking stuff in and out of the centrifuge.

- When using silica spin columns, you need to wash probably 3-4 times with 700 uL of wash buffer instead of twice. Vacuum manifolds leave more guanidinium on the sides of the tube which means more washing required. Basically, you will run through more wash buffer.

- The vacuum manifold is AWESOME for doing multiple larger columns, midi’s, maxis, nickle columns. The larger volumes of buffers you’re used to putting through those columns wash away anything on the inside just like normal, except this is WAY faster than gravity.

Nice design!

I’ll try to build my own soon, I’ll keep you posted ! Many thanks for this idea.